The ‘silver circle’ – a termed coined by The Lawyer in 2005 to define an elite group of City firms that were distinct from the magic circle – is now common parlance in the profession, but there is a problem. The silver circle as it was originally conceived has broken up, and members have gone one of two ways as their single road bifurcated (one, however, staggered off into the undergrowth and died in a ditch).

What does the silver circle look like now? Which firms still fit the definition? Are there new entrants to the club? And is the silver circle even a valid term any more?

Definitions and semi-circles

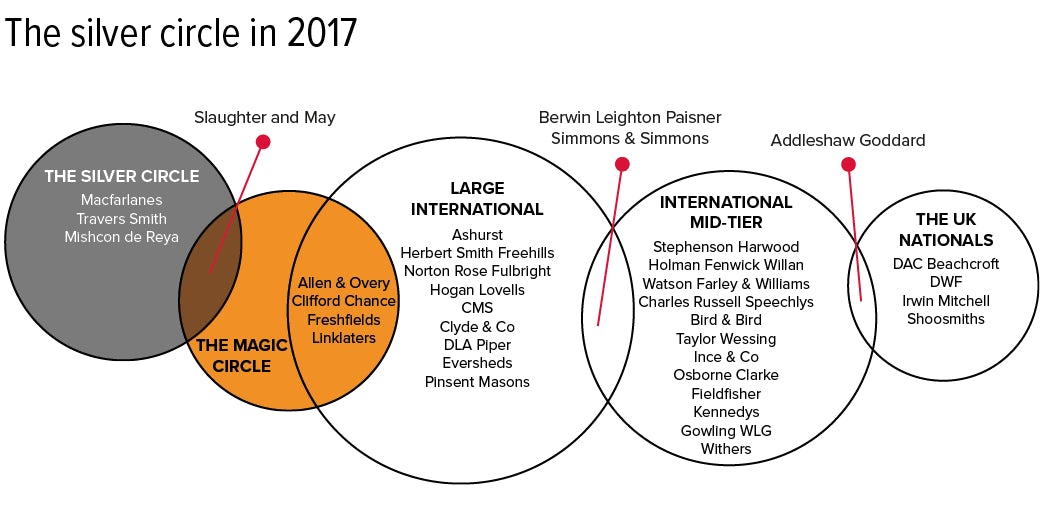

The silver circle was initially conceived as a tight group of firms, but the lines have blurred over time. Wikipedia (incorrectly) claims that The Lawyer originally defined the silver circle as Ashurst, Berwin Leighton Paisner, Herbert Smith Freehills, Macfarlanes and Travers Smith “with Hogan Lovells, Norton Rose Fulbright and Simmons & Simmons also sometimes included as members of the group”. As the term gained popularity recruiters would commonly ascribe silver circle status to any largish City firm outside the magic circle. A snap survey of our readers conducted this July suggests that a section of the legal market considers the silver circle exactly that: “magic circle wannabes”, to quote one respondent.

In fact, that was never the thinking behind the term. The silver circle was intended to define a category of firms with a similar approach.

The Lawyer editor Catrin Griffiths’ definition in 2005 read: “Silver circle firms are content to advise a premium UK client base rather than service global institutions. A lot of work is private equity-dominated […] it is sexy and it pays. By the way, there is something else that characterises these firms: a disdain for an overtly managerial approach and a horrified avoidance of big firm bureaucracy.”

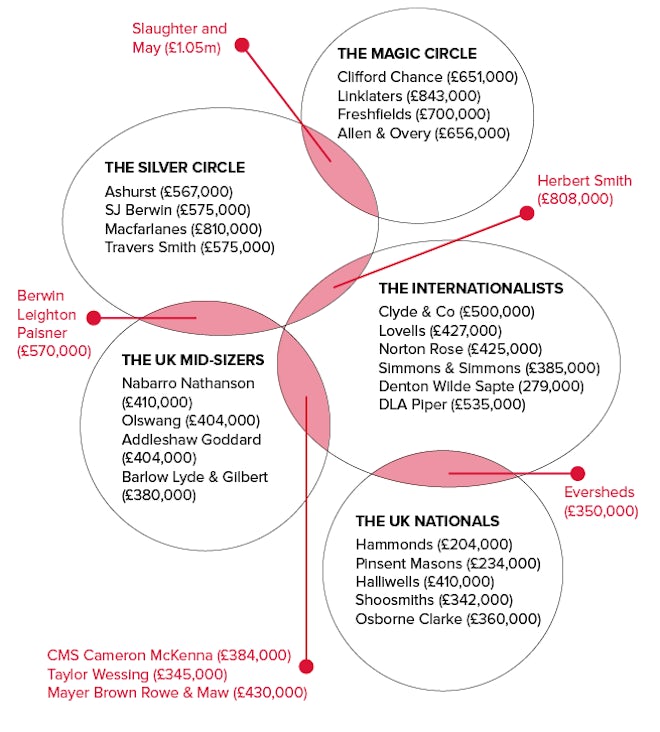

As firms that were international in their ambitions Lovells and Norton Rose, even before their game-changing US mergers, simply did not fit the bill and were put instead into an ‘internationalists’ bracket that also included DLA Piper, Clyde & Co, Simmons and Denton Wilde Sapte.

The members of the silver circle were also distinguished by the fact that they ranked below the magic circle in terms of turnover but could boast an average profit per equity partner (PEP) and average revenue per lawyer (RPL) far above the UK norm. With that in mind The Lawyer initially named only Ashurst, Macfarlanes, SJ Berwin and Travers Smith as the silver circle’s four core members. Herbert Smith – at that point stuck in a sterile European alliance with Gleiss Lutz and Stibbe and with only small outposts in Moscow, the Middle East and Hong Kong – was semi-included as being an “internationalist with silver circle traits”. Berwin Leighton Paisner (BLP), meanwhile, was only on the fringes as a kind of ‘associate member’. “Not yet well enough established to merit full membership” was our verdict.

From the archives: the original definition of the silver circle

“While the international firms have stuttered, the focus and the sheer ambition of a handful of formerly sleepy mid-size firms has transformed the market.

“While the international firms have stuttered, the focus and the sheer ambition of a handful of formerly sleepy mid-size firms has transformed the market.

As The Lawyer reported in its news pages this summer and last, the firms powering up the profit and revenues tables are Berwin Leighton Paisner (BLP), Herbert Smith, Macfarlanes, SJ Berwin and Travers Smith. BLP and SJ Berwin show what a little bit of drive and a focus on core principles can do. Macfarlanes and Travers Smith, meanwhile, have long pedigrees in the City – but never underestimate the difficulty of maintaining that position.

So what links them? Silver circle firms are content to advise a premium UK client base rather than service global institutions. A lot of the work is private equity-dominated, but there is a good amount of AIM business and a whole lot of real estate. It is sexy and it pays. By the way, there is something else that characterises these firms: a disdain for an overtly managerial approach and a horrified avoidance of big firm bureaucracy.

It is our thesis that Slaughter and May straddles the magic circle and the silver circle. Yes, it has the same international kudos as the magic circle firms, but its cultural and economic model is actually closer to Macfarlanes’ than Clifford Chance.”

Catrin Griffiths, editor, The Lawyer UK 100 Annual Report 2005

THE SIVER CIRCLE IN 2005:

Moving out

There is little question that the group of firms that made up the original silver circle have taken differing paths. Three pursued their international aspirations while two remained UK-focused.

Ashurst has left the silver circle to become an international firm, but maybe it would have been better off staying put. The firm won a symbolic battle by keeping its name in the merger with Blake Dawson but, according to The Lawyer Global 200 2016, 38 per cent of the partnership is based in Australia and 33 per cent in the UK.

To be fair, the firm always declared that it was something else. Back in 2010 former managing partner Simon Bromwich was already disavowing that his firm belonged in a bracket with Travers and Macfarlanes, saying: “Those are excellent firms but their strategies and ours began to differ markedly well before 2005, as Ashurst embarked on a much more extensive international push.”

By choosing to pursue that international strategy, Ashurst joins that group of firms that includes Hogan Lovells, Norton Rose Fulbright and Herbert Smith Freehills (HSF). The only real difference is that Ashurst has been less successful.

A section of the legal market considers the silver circle as ‘magic circle wannabes’. That was never the thinking behind the term; it was intended to define a category of firms with a similar approach

Revenue doubled when the firms combined but turnover then immediately fell over two years by 14 per cent, from £586m to £505m. PEP plunged nearly 25 per cent, from £801,000 to £603,000 in 2016, the lowest recorded by the firm in over a decade. Worse, Ashurst’s top of equity fell below £1m that year, a benchmark achieved by every one of its rival UK top 10 firms. While PEP has recovered somewhat, it is no longer at silver circle level.

Always more internationally minded than the ‘classic’ silver circle firms, Herbert Smith also moved gradually further away from the definition, cutting any lingering ties with the group for good by becoming HSF in 2012. Though like Ashurst it lacks weight in the US, its Aussie tie-up has proved more successful. Revenue has continued to climb post-merger. The firm’s PEP has held up better than Ashurst’s too, though Travers passed Herbies on this measure in 2013 and in every year since. But however you slice it, HSF simply does not look like a silver circle firm anymore. It has morphed into an international giant, a different beast entirely.

The third and final silver circle firm to pursue an international agenda was SJ Berwin, about which the less said the better: the sorry tale of the firm that became King & Wood Mallesons (KWM) has already been told in these pages. Needless to say, KWM 2.0, the part of the firm that survives in London, does not qualify for membership of the group in 2017.

One of these things is not like the others: the case of BLP

Always the most fringe member of the silver circle, in 2005 we said that BLP had a shot at gaining full membership of the club. That was during its glory years – the firm was on the up at a time when real estate was sexy and key client Tesco was also booming.

Tesco has faltered in recent years and BLP has too. It looks less and less like the rest of the silver circle. Its revenues are significantly bigger but its profits are significantly smaller. AveragePEP of £630,000 in 2017 is strong compared with the wider market but certainly not in Macfarlanes’ or Travers Smith’s league.

Its strength in real estate is unquestionable but it does not match the reputation of Travers or Macfarlanes when it comes to taking on the high-end corporate instructions. Like Ashurst, it has made international moves but found full consummation with a US firm hard to come by.

Profit doesn’t lie

Which leaves us with the two firms that have not pursued the international dream. Combining high profits, a top-tier corporate practice, a clubbable attitude and a fiercely independent mindset, Macfarlanes and Travers Smith are the two original members of the silver circle that remain resolutely in that bracket.

Neither firm has opened offices across the world, with Travers’ small Paris outpost the sum of their combined globalisation efforts. Like the magic circle, their clients come from all over the world but they have done it without merger or flag-planting, and there is a strong UK focus to their work.

Perhaps most tangibly, the two firms outperform their rivals in terms of PEP. When once their average equity partner profits were broadly similar, over the past half dozen years Travers and Macfarlanes have pulled steadily away from Ashurst, BLP and Herbies.

Since 2005 average PEP has increased by 69 per cent at Travers Smith and by 70 per cent at Macfarlanes. In the same period PEP has risen just 19 per cent at Ashurst and 11 per cent at BLP, and it has decreased 6 per cent at Herbies. Nor is this a one-off, 2017-only phenomenon: a five-year average shows Travers and Macfarlanes well ahead of the others.

Metrics show that Macfarlanes, Travers Smith and Mishcon are true silver circle firms, distinct from the likes of Herbert Smith Freehills, BLP and Ashurst

Form a circle

Thinking of other runners and riders, Hogan Lovells and Norton Rose Fulbright – the two other names commonly cited as silver circlers – have only become more international due to major US mergers and thus do not fit the criteria.

But there is one firm that qualifies for silver circle status on every count: one that has come from way back in the field. When the silver circle was first coined in 2005 Mishcon de Reya was nowhere – just another smallish City firm. That year it ranked 78th in The Lawyer UK 200, just behind Bircham Dyson Bell. It had revenue of £24.2m and PEP of £295,000.

In 2016 it ranked 31st in the UK 200, rising in the charts for the 11th year in a row. It reported revenue of £151.8m and PEP of £1.1m in its latest set of financial results.

This rise up the revenue charts is dramatic if not unprecedented, and puts the firm squarely in the Macfarlanes and Travers size bracket, while the PEP figure in excess of £1m definitively cements Mishcon’s position as a fully paid-up new member of the silver circle. Unquestionably, Mishcon is a different beast from those firms in that it is a litigation rather than a corporate/finance firm first and foremost.

However, it is similar not just because of its profit figures but also because it is still primarily a London firm.

Whichever way you slice and dice it, Mishcon, Travers and Macfarlanes come up together in a group in a way that the other firms do not. This fact alone suggests that those who claim there is “no such thing” as the silver circle are mistaken. What we have are three firms distinct from the rest of the market in terms of profile and in strategy.

“It’s not a term we use, either internally or externally, to describe ourselves,” says Travers Smith managing partner David Patient. “But while we would probably not say ‘we are part of the silver circle’ that is not to say it’s necessarily unhelpful, and I think the term is picked up by foreign law firms. If you’ve got a definition for a certain type of law firm and you want to put firms in that basket I have no objection at all.”

Depth, not breadth

The metrics of revenue, PEP and headcount speak for themselves but silver circle membership has never been entirely scientific: other less tangible factors play a part too. The word ‘prestige’ is a loaded one but it has to be to be mentioned. The respondents to The Lawyer’s survey certainly did. As one survey respondent put it, true silver circle firms must be “top tier in quality. Depth, not breadth”. For better or worse Macfarlanes and Travers both exude an aura of exclusivity that many other similarly- sized firms do not. Part of that is down to profits, part of it is down to the type of corporate transactions they are able to take on despite their smaller size. Part of it, perhaps, is down to marketing and an old-school reputation.

Significantly, Mishcon matches Travers and Macfarlanes in the prestige stakes. From its famous founder, Lord Mishcon, through the days when it acted for Princess Diana on her divorce (“Mishcon de Reya: thirteen letters to strike fear into any man’s heart,” The Times’ Slummy Mummy column once quipped) to the present day, the firm has always had the veneer of glamour. Its work on the Article 50 litigation cements its position as a firm to go to when you have a problem that really matters. The fact that it built a reputation on family law and contentious matters as opposed to corporate transactions is no barrier to its presence in the silver circle: after all, Macfarlanes maintains its successful private client practice despite its corporate capacity.

The elephant in the circle

There is, of course, one large and extremely profitable elephant in the room. We need to talk about Slaughter and May.

Slaughters fits the silver circle bill in every respect. London-centric, sky-high PEP, top-tier work, an aura of prestige: Slaughter and May is far more like Macfarlanes that the magic circle quartet it is commonly lumped in with. To put it in the same category as Allen & Overy, Clifford Chance, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and Linklaters would be inaccurate, and to say it is in a class of its own is frankly showing the firm too much deference. The times are changing. In February 2017 Slaughters made its first-ever lateral hire in London, taking on HSF head of pensions Daniel Schaffer. It manages performance like any other firm. It is not some mystical Camelot.

If you think of silver circle firms as “magic circle wannabes” you may well baulk at the idea of ‘demoting’ Slaughters. But the silver circle members clearly are not wannabes. They are pursuing a different way of doing business. And on that score, Slaughters fits in perfectly.

The future

It seems unlikely that any other firms might join the silver circle any time soon. Returning to our feature of 2005 we named 10 firms to watch as ones that could make the cut in future. None have. Clydes, CMS Cameron McKenna and DLA Piper pursued global ambitions. Ditto Rowe & Maw – then fresh into a merger with US firm Mayer Brown – and Wragge & Co, now Gowling WLG. Olswang and Nabarro have both been swallowed up by CMS.

The final two firms, Addleshaw Goddard and Taylor Wessing, have kept their names but neither has pushed on enough to merit inclusion. Similarly, a group of City firms with a broadly similar profile – Bird & Bird, Fieldfisher, Osborne Clarke and Simmons – quite simply come nowhere near Macfarlanes or Travers in terms of PEP. And anyway, they are all pursuing international strategies to a greater or lesser extent.

Large London-only independent firms in the mould of Macfarlanes are thin on the ground. So is there a future for that model?

“The independent path we have taken is one we are comfortable with, and one that has worked extremely well for us,” says Patient. “In 2005 there might have been a question mark in the eyes of some people as to whether it was a sustainable model because everyone else seemed to be doing something different in pursuing their international ambitions. Now, most people would recognise this is a credible alternative way of operating a legal business. You only have to look around the world to see the number of top quality independent law firms there are, and these firms have got better at working with each other.”

“Internationally, our model has proved strategically highly valuable,” adds Macfarlanes senior partner Charles Martin. “The quality of work we can do for our clients around the world – and the work inbound from the independent firms around the world with whom we work – is of a far higher calibre than would be realistic for us to deliver or generate ourselves.

“One day the international firms may vie with us on consistency of quality for complex work across multiple jurisdictions great and small, in which case our competitive advantage will become eroded. But today, we are pretty clear that what we offer has distinct advantages for our clients and ourselves.”

Patient continues: “If you take the largest global law firms, how many offices do they have. Forty? Seventy? We worked in over 100 countries last year. How are the global firms working in those other countries where they don’t have a base? In the same way we do. Our offering gives clients the opportunity to select the most appropriate adviser in any jurisdiction.”

As for how the silver circle will develop, “this market never stands still”, says Martin. “Client demands change year on year, and firms who consider themselves to be in the silver circle today must remain vigilant and agile in their response to those needs. This isn’t a comfortable part of the market to operate in and any loss of focus will quickly be punished.”

Readers’ reaction: definitions and perceptions

Part of the problem with defining the silver circle is that there is a difference of opinion as to what it is, exactly.

When it coined the phrase The Lawyer was clear it was a group of UK-centric firms doing high-quality work and with high profits, but without the giant revenues and international scope of the magic circle.

We surveyed our readers to see what they thought defined the silver circle, and a clear group adhered to our original criteria…

- “High profits, top-tier in quality. Depth, not breadth”

- “High PEP, large UK-based revenues”

- “Quality law firms of a certain size that are not magic circle but stand out from the rest of the firms in the UK

- “UK firms headquartered in London, a clear step below the magic circle in terms of profit and so on, but still excellent quality and high profit”

- “Not as elite as magic, not American, not big and global like DLA/SPB”

- “A firm with similar or slightly less prestige than the magic circle firms with a good range of corporate and finance practice areas. Must have high PEP (£750,000ish-plus). Another condition is having a smaller international footprint than the magic circle which tends to put a firm in a quite different market position – for example, Macfarlanes, Slaughter and May, Travers Smith”

But another set of readers had a different definition – to quote one of them, “magic circle wannabes”. This group sees the silver circle merely as the biggest firms outside the magic circle…

- “International, London-headquartered, full-service firm with revenue, size and profitability a tier down from magic circle. Generally, similar geographic coverage, business model and culture to the

magic circle” - “Magic circle wannabes (in terms of prestige, profits, and global footprint)”

- “Very big City”

- “Next five firms outside the top four”

The result? A mixed message, with a diverse group of firms – including several that never fitted into the original definition – embedded in the profession’s idea of what the silver circle is.

Americans in the silver circle? For more on international firms’ influence on the silver circle click here

Comments